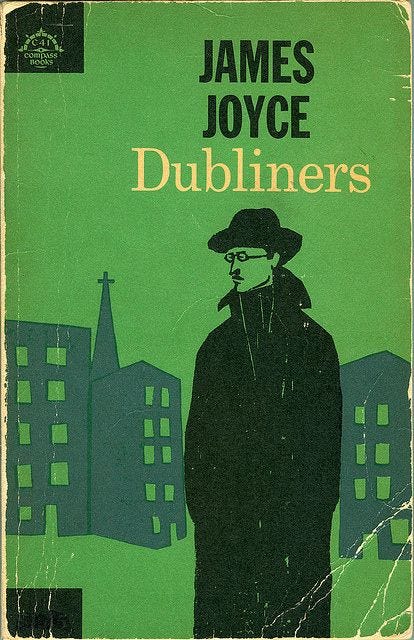

araby by james joyce

an examination of a short story about the most intense puberty awakening ever in Joyce's novel Dubliners

PRELUDE

As someone who believes that Christianity and traditional structures have formed the foundation of most storytelling (particularly in Western cultures and even some Eastern ones due to the influence of colonialism) I was especially drawn to James Joyce’s “Araby,” a chapter and stand alone short story in his book Dubliners. In this story, Joyce weaves themes of religion, myth, and societal forces into the protagonist’s journey of awakening, as seen through his realization that his young puppy love is utterly shattered. It resonated deeply with me as a story about coming of age without shying away from the harsh, stark realities, but also since visiting Ireland has always been my dream! In this article, I dive into Joyce’s portrayal of consciousness and the clash between idealism and reality.

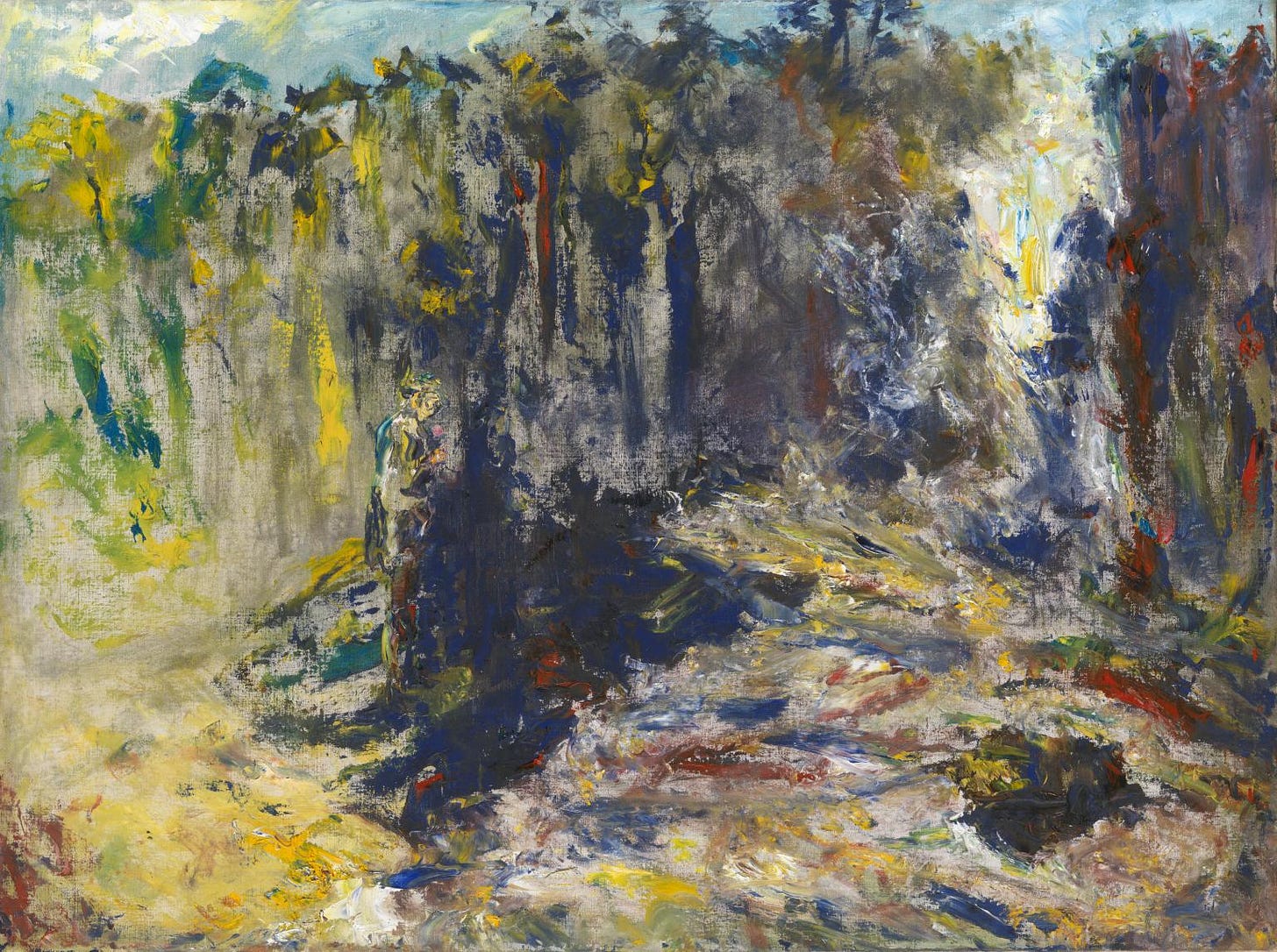

Throughout the post I feature works by Jack Butler Yeats, an Irish artist! All photos are courtesy of the Tate Modern.

SMALL BITES

Before we begin, here are a few literal bites of what I’ve been cooking and eating up lately 😋

🐙 okinomiyaki

Highly underrated Japanese fried drunk food. Super easy to make! I highly recommend trying to make this at home, I was very pleasantly surprised.

🧣 cinnamon rolls

It’s officially sweater weather and we got these delicious cinnamon rolls from Trader Joe’s~

🐟 danish rye bread and herring

A lethal combo and simply the best thing ever. My love for pickled things and seafood I think only further proves myself as a Korean (and maybe a Dane in my past life…)

WORDS

James Joyce brings forward the idea that human existence is shaped by stories that provide order and meaning amid inner emotional turmoil. In his short story “Araby,” Joyce examines his protagonist’s journey toward consciousness, utilizing mythic and religious storytelling to reveal the underlying structures that saturate the human experience. The young boy’s quest for love, framed as a romantic and adventurous crusade, mirrors the structure of myths and is infused with traditional symbols and religious narratives. However, Joyce’s approach fragments this ideal, presenting a stark reality where the self is dehumanized and fractured, no longer unified. The boy’s disillusionment at the bazaar marks a moment of heightened self-awareness, a realization that his desires and actions are entangled in forces beyond his control: imperialism, capitalism, and religion. This inward turn, characteristic of modernist literature, explores the complexity and ambiguity of consciousness in a fragmented world. In “Araby,” James Joyce carefully examines the boy’s evolving consciousness, as seen in the story’s final passage of the boy’s transformative awakening at the bazaar. By underscoring strong religious imagery, careful diction, and sensory details, Joyce captures the convergence of the stories told around capitalism and Catholic social order, revealing the intricate ways in which personal desires are shaped by societal forces.

The boy views the Araby bazaar as a mystical, exotic symbol of the East, romanticizing it as the backdrop for his chivalric mission. His promise to return from the bazaar to bring Mangan’s sister something from the bazaar mirrors the vows of knights in their quests and crusade, but the idealized mission is quickly undermined by the commercialization of his romantic desire. The theme of consumerism and materialism comes to a head in the story when Joyce employs the repeating motif of coins. When the boy enters the bazaar and Araby turns out not to be the fantastic palace he had imagined, he sees “... two men were counting money on a salver. I listened to the fall of the coins” (Joyce 31). The coins distract him at the bazaar as the descriptions are followed by his remark: “Remembering with great difficulty why I had come I went over to one of the stalls…” (31). This motif is repeated after the boy’s epiphany as well, as he turns to leave the bazaar he states “I allowed the two pennies to fall against the six-pence in my pocket” (Joyce 32). Joyce specifically draws attention to the repeating image of falling coins. The boy's affection for Mangan’s sister becomes reduced to the purchase of a token, suggesting that consumerism has distorted the internal expression of affection and devotion and that expressions of love can be contained in physical, external objects and traded like commodities. This commercialization is further complicated by religion.

Joyce utilizes Christian themes and imagery to describe the boy’s disillusionment. From his arrival the boy immediately and directly connects the space to an empty church, stating “I recognized a silence like that which pervades a church after a service.” (Joyce 31). Additionally, the auditory conjuration of coins echoed throughout the final passage is further complicated by Joyce's use of the word “fall,” evoking the fall of man, a Christian doctrine that describes Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden and consequential loss of innocence. When the boy is confronted by the young woman working at the stall, he turns and describes himself, “I looked humbly at the great jars that stood like eastern guards at either side of the dark entrance to the stall…” (Joyce 32). The boy actively personifies and brings the jars to life, comparing them to the Eastern angels guarding Eden. It is implied that the world beyond the bazaar is an expulsion from Eden itself and the boy’s self-employed use of the word “humbly” denotes a sense of guilt in his position. Thus Joyce insinuates that despite the boy’s original imagination of the journey as a crusade, he foreshadows that the boy is about to experience a “fall” from innocence.

The boy’s religious reverence clashes with subtle sexual undertones, as Joyce blurs the distinctions between religious devotion and romantic longing throughout “Araby.” This tension is evident when the boy approaches a stall at the bazaar, where a young woman, distracted by her conversation with two English men, only briefly attends to him, seen “At the door of the stall a young lady was talking and laughing with two young gentlemen” and “The tone of her voice was not encouraging; she seemed to have spoken to me out of a sense of duty” (Joyce 31-32). The boy’s idealized view of love, shaped by Christian notions of purity and devotion, is contrasted with the woman’s flirtatious interaction with the English men and disinterest in the boy, highlighting a disconnect between his expectations and reality. His romanticized, almost sacred, mission to procure a gift for Mangan’s sister is undermined by the superficial nature of the bazaar, where love and attention are trivialized and commodified.

The boy’s inability to reconcile conflicting forces of love and commercialization leads to profound disillusionment, which culminates in his epiphany at the story’s end. Joyce uses darkness as a way to mark the boy’s disillusionment and contrast against descriptions of Mangan’s sister, often surrounding her with light to emphasize her purity and elevate her to a near-divine status. Mangan’s sister, despite the darkness, is often described against the shadow and rather depicted as illuminated, as the boy remarks “her figure defined by the light” (Joyce 26). In contrast, the boy remarks upon his arrival at the bazaar, the seeming expansion of the darkness in the environment: “Nearly all the stalls were closed and the greater part of the hall was in darkness” (Joyce 31). In the final moments of the story as he gazes into the darkness, he sees himself as “a creature driven and derided by vanity,” shamefully recognizing that his romantic quest was ultimately driven by external forces—consumerism, religious expectations, and societal norms (Joyce 32). Joyce’s portrayal of the boy’s emotional and psychological awakening reveals the confusion and pain that arise when personal desires are shaped by a world that commodifies affection and distorts his perception of reality.

In “Araby,” Joyce intertwines themes of imperialism, capitalism, and religion with the personal desires and frustrations of the protagonist. The boy’s romantic quest, which at first appears to be a simple, youthful endeavor, becomes a complex narrative that reflects the broader forces shaping his world as he gains a sense of awareness or consciousness in his environment. Through Joyce's careful use of imagery, the boy’s journey exposes the commercialization of affection, the conflation of religious and romantic ideals, and the entanglement of personal identity with larger socio-political structures. The boy’s ultimate disillusionment at the bazaar reveals the hollowness of his quest and the deep, often painful, awareness of how external forces manipulate individual desires. By the end, Joyce highlights how the tug of modernity and tradition, commerce, and imperialism infiltrate even the most intimate aspects of human experience, leaving the boy—and readers—contemplating the complexities of love, identity, and societal influence.

Thanks for reading!

Skylar xx

![[banchan]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bzBv!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4020a6b2-7d75-439c-8957-0777f2e5fe65_1200x1200.png)

![[banchan]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!bzBv!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4020a6b2-7d75-439c-8957-0777f2e5fe65_1200x1200.png)